Copper (Cu) is required in very low quantities for broilers, with requirements ranging from 3 to 10 ppm of copper. In countries outside Europe, this mineral is, however, supplemented at growth-promoting levels (80 – 200 ppm Cu). These high levels can interfere with the chelation between the mineral and phytic acid, also known as phytate. What are the interactions between Cu, phytase and phytic acid?

Phytate (inositol hexaphosphate), which is commonly found in plant-based feeds, is a compound accounting for 60-80% of the total phosphorus of a plant. The anti-nutritional impact of phytate extends to the chelation of divalent minerals (e.g., Zn2+, Ca2+, Cu2+), rendering them insoluble (Osunbami & Adeola, 2025).

The use of exogenous phytase has been consistently proven to enhance phytate degradation. As a result, P and other minerals (such as Zn and Mn) are released from the phytate present in the feed. Nevertheless, its effectiveness is influenced by dietary factors, gut pH and the complex interactions between nutritional and physiological conditions.

Figure 1 – The IFCN World Feed Price.

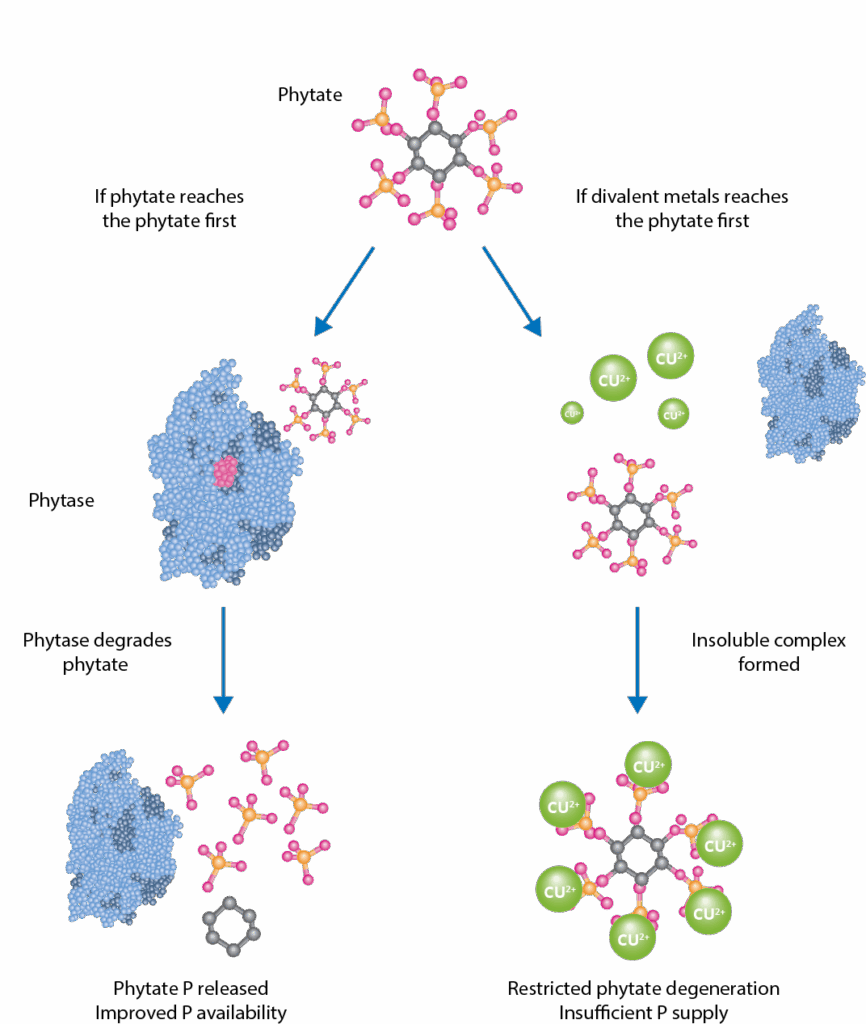

The mechanism of mineral–phytate complexation is complex because multiple interconnected factors control it. The pH determines both the charge state of phytate and the solubility of the mineral, thus influencing the strength of their interaction. At the same time, mineral solubility limits how much divalent mineral (e.g., Cu²+, Zn²+) is available to form complexes. Finally, the activity (velocity) of phytase, which degrades phytate, is affected by both pH and mineral levels: optimal enzyme activity occurs only under conditions where Cu²+ or Zn²+ does not precipitate or strongly inhibit the enzyme. These overlapping effects create a dynamic, pH-dependent system where the extent and nature of mineral–phytate complexes can vary significantly (Figure 1).

Phytate–mineral complexation

In monogastric animals, high dietary levels of Cu and Zn are known to impair phosphorus digestibility through 3 main mechanisms:

- direct inhibition of phytase activity,

- formation of insoluble mineral–phytate complexes that are resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis, and

- alteration of digestive conditions, such as increasing buffering capacity, thereby limiting the reduction of stomach pH.

In piglets, this effect on phosphorus digestibility was recently highlighted in a meta-analysis (Labarre et al., 2025). Diets were supplemented with 1,000 FTU of phytase. When piglets were supplemented with 2,500 mg of Zn/kg of feed, P digestibility was reduced by 26% compared to piglets fed 100 mg Zn/kg of feed.

In broilers, it was reported that supplementation with 250 ppm Cu from divalent CuSO₄ markedly reduced phosphorus digestibility: by 19% when 600 FTU of phytase were included in the diet, and by 29% when no phytase was provided.

Both trials demonstrated that high levels of Zn and Cu affected P digestibility, with the effect being more pronounced in the absence of phytase supplementation. Given that phytate exhibits a stronger affinity for divalent cations, could copper in a monovalent form potentially mitigate these interactions and thus exert a lesser influence on phytase activity? To explore this topic, some studies were performed.

Figure 2 – In vitro effect of Cu sources on phytic phosphorus released by phytase at pH 4.5.

Figure 3 – In vivo effect of Cu sources bone mineralisation in broilers.

Phytate–Cu complexation

An in vitro trial conducted at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona investigated the impact of Cu sources — monovalent Cu oxide versus divalent Cu sulfate — and dosage (0, 15, 150, or 300 mg Cu/kg) on the phosphorus released by phytase. At pH 4.5, the study showed that divalent Cu sulfate reduced the phytic phosphorus released by phytase more than monovalent Cu oxide, with a 10% difference between the sources. The reduction in phytic phosphorus release became even more pronounced when Cu supplementation exceeded nutritional levels (150–300 mg Cu/kg).

In vivo study in South Africa

To confirm the in vitro results, an in vivo trial with 2000 birds was performed in a research station in South Africa to compare two different Cu sources at 200 mg Cu/kg in diets supplemented with varying doses of phytase (0, 500, 1000, 1800, 2500, 3500 FTU from a fast-acting phytase) on bone mineralisation. The results showed that at low doses of phytase, the monovalent Cu resulted in fewer interactions of free soluble Cu with phytate, thus reducing the impact of copper on phytase efficacy. These results could be amplified if the phytase used were a slow-acting enzyme. Therefore, nutritionists using lower doses of phytase should be cautious of the impact of divalent Cu on phytase efficacy and matrix values applied in practice.

Take-aways

The interaction between copper and phytate is highly complex, and it is influenced by several key factors, including the type of phytase, its release profile, the source of copper, and the dosage applied. Both phytase and copper superdosing require careful consideration. While phytase superdosing can alter the dynamics of phytate breakdown, excessive use of divalent copper as a growth promoter may compromise phosphorus availability. Therefore, selecting the right combination of phytase and copper source is essential to optimise nutrient utilisation and prevent economic losses, with priority given to monovalent Cu sources and trace minerals that dissolve more slowly.

References available upon request